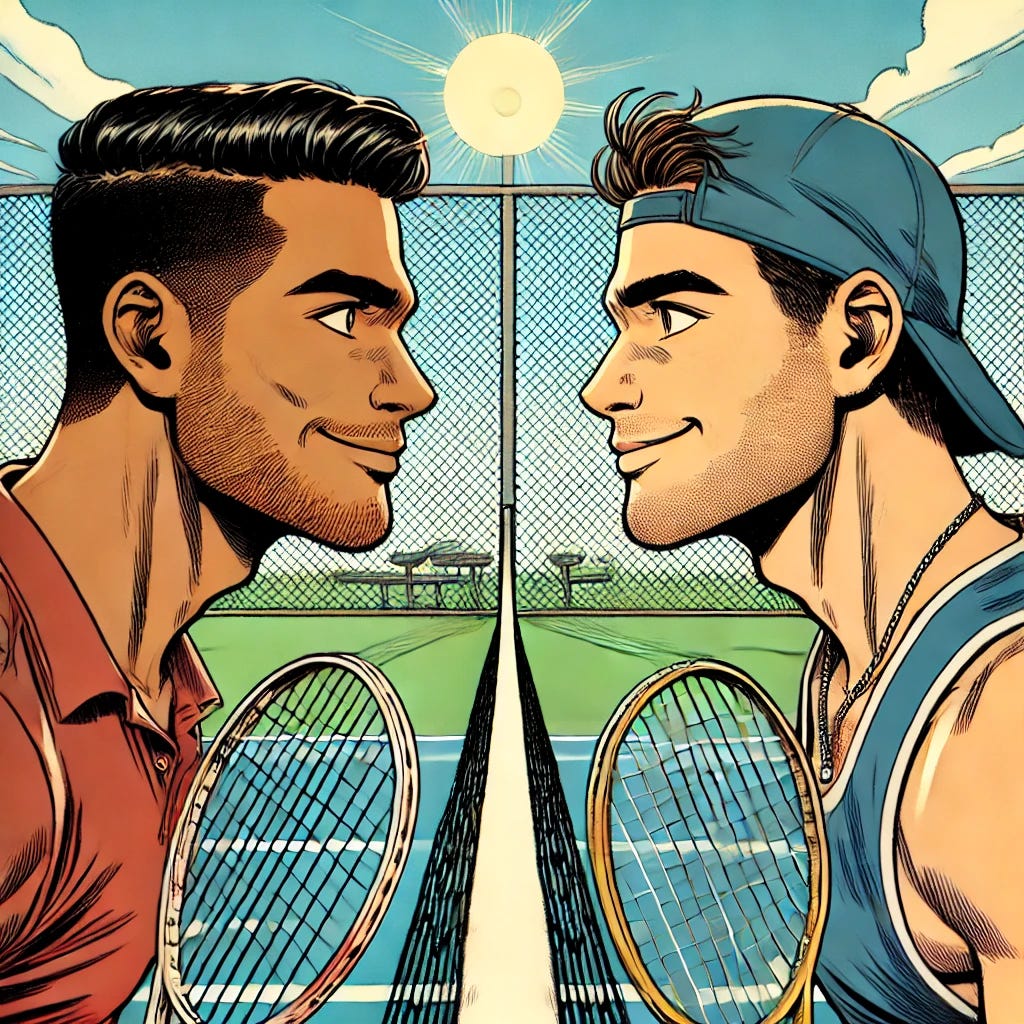

In tennis, who is it that provides a person with the obstacles he needs in order to experience his highest limits? His opponent, of course!

Then is your opponent a friend or an enemy?

He is a friend to the extent that he does his best to make things difficult for you....[giving you] the opportunity to find out to what heights you can rise.

-Timothy Gallwey, The Inner Game of Tennis

As the U.S Open tennis championships approach1, I often reflect on the lessons from my time as a nationally ranked junior player. Many of those lessons came from painful losses such as this one:

At sixteen, I stepped onto the court in my Nike gear with a paradoxical mix of emotions—overconfidence fueled by having my best ranking ever and an underlying fear that I wouldn’t live up to the expectations of my ranking in this tournament in Palos Verdes.

As these emotions swirled, the match quickly spiraled out of my control. My opponent, who should have been a straightforward win, played the match of his life. His shots painted the lines and he couldn’t miss his serve. Meanwhile, on my end, everything that could go wrong did. My shots were off and there was a gusty wind that seemed to always pick up when I hit, sending the balls in unintended directions—I was unraveling.

Anger surged through me—fury at the thought of losing to someone I knew I could beat. My mind wasn’t on the match; it was locked in a battle with itself, replaying every mistake.

In a pivotal point in the second set, my opponent called one of my shots out that I thought was in.2

My frustration boiled over—I threw my racket, sprinted to the net, and hurdled it like Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone. I stood over my opponent, fists clenched…But then I caught a glimpse of my dad through the fence, his face in disbelief. That look stopped me from doing something I would have regretted, but the damage had been done…I had completely lost control of my mental game and eventually lost the match.

Fixated on winning and terrified of how I’d be perceived if I lost, I forgot one of the most important lessons of the game: point-by-point focus...stay in the moment and don’t dwell on points won or lost.

It also taught me another less intuitive lesson: Our opponents can either be our adversaries or our allies. I saw my opponent that day as an adversary - his exceptional play was a threat, which made me lose focus on what I could control and start looking for things to blame (my opponent playing out of his mind, the wind, cheating, my busted backhand).

Leadership Principle: Those who oppose you who can be your adversary or ally. By approaching them as allies, you increase the odds that you achieve your desired goal.

So what would it look like to have seen my opponent as an ally?

Timothy Gallwey’s quote above nails it. I could see my opponent’s outstanding play as an opportunity for me to “find out to what heights I can rise.” By adopting this mindset, it would have allowed me to shift from fixating on winning to focusing on making the right efforts to win in light of the obstacles.

So, how is this relevant for organizational life?

We all have colleagues who feel like opponents—those with conflicting goals or interpersonal issues. In high-stakes situations, their actions (or inaction) create friction, leading us to see them as adversaries.

But we do have a choice. Instead of adversaries, we can view them as allies who challenge us to perform at our best, seeing their competing agendas as opportunities for us to grow our “influencing and navigating conflict” muscles. By shifting our mindset, we learn to love the friction and focus more on our approach to resolving the conflict than on simply winning.

This powerful shift helps us move beyond a scarcity mindset where we only see obstacles and opens up possibilities for “win-for-all solutions,” where everyone, most importantly the organization, benefits.

The next time you find yourself in a situation where you need to influence an “opponent” - someone who is actively resisting you - my challenge for you is to see them as an ally.

Take Action: Proven and Practical Steps

Set a positive intent. First, reframe your “opponent” in conflict as an ally in learning and growing (vs. an adversary to defeat). Second, focus on making the right efforts to get the outcome you want (vs. fixating on winning or losing). Third, commit to seeking a win-for-all-solution.

Analyze all dimensions of your opponents’ game: Embrace your curiosity and seek to uncover the specific motivations, priorities, agendas and emotions that might be “at play” for your opponent(s). Seek to understand who they respect and who has influence over them. Take the time to write these things down. Ideally, you will have built a foundation of trust with this person prior to this interaction as that can make it easier to see them as an ally; however sometimes this step gets skipped or we don’t have the luxury of time.

Make an action plan that anticipates roadblocks and enlists others who can support you. Using what you’ve learned from your “analysis,” see if you can come up with creative “win-for-all” solutions. You can start by answering questions like “What resources are available to us that we haven’t used? How else could you think about this? If you were the other party, what would you propose?”3 Then once you have some ideas, anticipate where there might be resistance from your opponent and literally script out how you will respond to them. Also, reach out to others that can help you win over this ally. Finally, rely on air cover from someone more senior (e.g., the CEO or Board Chair) as a last resort.

Reflect: Some Questions to Consider

Who is an “opponent” in your organization that you currently treat as an adversary? What would it take to see them instead as an ally?

What are their motivations, priorities, agendas, emotions and network? If you don’t know, how can you learn more about each of these?

What actions can you take to maximize the odds that you achieve a win-for-all solution?

If this week’s Friday Reflection was practical or enjoyable (or maybe even both!), please share it with your colleagues and friends.

The US Open is handsdown my favorite New York City event. This will be my 20th year attending! It’s an amazing experience even for non-tennis players - so much joy, triumph, and greatness. And the Honey Deuces are pretty good too :)

Most junior tennis matches do not have umpires. It’s an honor system for calling shots in and out. In the pros, they have technology that umpires rely on and over time I imagine this technology will get cheaper and be used for junior matches too. In this case, I don’t know for sure that my opponent cheated…I was so mad that I was looking for things to blame. But in other matches, there were players who were notorious for cheating…blatantly calling balls out that were clearly in. They did it as a headgame. Lots of lessons from playing those matches too…and maybe some of those stories can be used in a future reflection.

These questions come from a book I often cite, Jim Dethmer and Diana Chapman’s 15 Commitments of Conscious Leadership. They have entire chapters on “Experiencing the World as an Ally” and “Creating Win for All Solutions.” As simple as some of these commitments are in concept, they are quite challenging to consistently live out in practice. It is hard to live what we know.