Believe it or not…Disney was vehemently against director Jon Favreau’s desire to cast Robert Downey Jr. as Iron Man.1 If he had tried to keep everyone happy at the studio, Favreau (and all of us fans) would have missed out on one of the most epic characters in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) and perhaps, may have never spawned the multi-phase franchise that is still running strong 15 years later.2

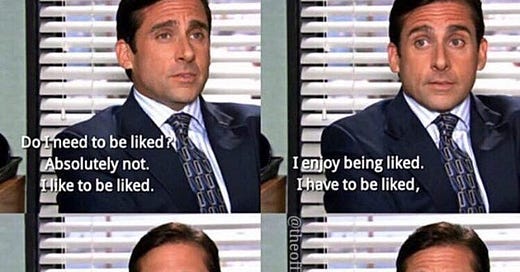

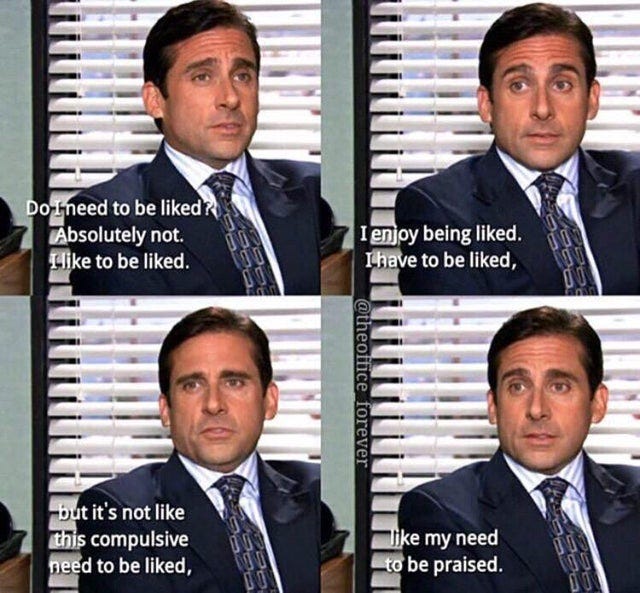

Making unpopular decisions (like Favreau’s choice) can be difficult for all of us. It is particularly hard for leaders whose dominant acquired need is affiliation.3

This week’s reflection goes deeper on the topic from last week on motives and decision-making. As promised, we’ll explore decision-making watchouts and techniques for leaders that have each dominant motive profile: affiliation, achievement and power.

Let’s start with affiliation.

One recent example illustrates many of the decision-making pitfalls of an affiliation-dominant leader:

A CEO asked her team to decide on a multi-million dollar bet on an emerging technology. She had a strong hypothesis on which technology to back, but two of the leaders on her team seemed to disagree. One of those leaders was her trusted lieutenant who had built a strong relationship with one of the other companies they were evaluating. The other was a charismatic yet underperforming leader, whom she had been meaning to put into a different role for the last two quarters but just hasn't gotten around to it. The rest of the team agreed with her strong hypothesis. In the meeting where the team was supposed to decide, the CEO could tell that the team was not on the same page and told them that they would discuss it more in next monthly leadership meeting. Two weeks later, a competitor acquired the preferred technology, which meant they ended up settling for an investment with inferior capabilities, and were badly beaten by their competitor in this category.

Watchout 1: Overly rely on consensus to arrive at a decision. Affiliative leaders tend to care deeply about bringing people together, invest heavily in team cohesion and seek to draw out all perspectives. As a result, they are often more comfortable with making decisions by consensus. The challenge with overly relying on consensus is that it prevents teams from moving quickly.

Technique 1: Consensus deadlines. Set hard deadlines for your team to get aligned on decisions and if they cannot reach consensus by that date, then you as the leader make the final call.

…

Watchout 2: Struggle to separate feelings about people from substance/business issues. Because they are so attuned to people’s feelings, affiliative leaders have the habit of overweighting those feelings relative to other important data points. The cost of this watchout can be catastrophic as it can lead to the wrong decisions.

Technique 2: Substance vs. emotion. Draw a simple T chart with left side of the chart being “substance” and right side as “emotion.” List out the data and facts on the left side (e.g., technology X has better feedback from customers) and the people related issues on the right hand side (e.g., Marta will be upset since technology Y has been her pet project). Then ask yourself two questions:

What are the risks of not addressing the emotional side?

How can you mitigate these emotional risks while still pursuing the best substance option?

There will be some cases where not addressing the emotional side is problematic (e.g., a high performer who is disgruntled by a decision may decide to look for a job at a different organization). This would be extremely costly. The reason the second question is so powerful is that there may be other actions that you can take to address their concerns and make sure they feel supported, while still taking the best substance decision.

…

Watchout 3: Avoid or delay unpopular decisions. Because affiliative leaders have a hard time feeling like they are letting others down, they tend to avoid unpopular decisions like choosing to give resources to one division over another or replacing the loyal, well-liked yet underperforming leader on their team.

Technique 3: 10/10/10 analysis of indecision. This is a slight modification of a tool in Chip and Dan Heath’s book Decisive.4 They point out that you can overcome short-term emotion by attaining distance from the decision. My slight tweak on it is to attain that distance by looking at the cost of inaction. In other words, ask yourself:

What are the costs (financial, time, etc.) of avoiding this decision?

10 minutes from now, will it feel worth it to avoid this decision given the cost?

10 months from now, will it feel worth it to avoid this decision given the cost?

10 years from now, will it feel worth it to avoid this decision given the cost?

By adding distance, it will help you to see that making a tough decision is worth the temporary “suffering” of others disliking us or being angry with us.

…

Even if affiliation is not your dominant motive, my experience would suggest there are times for most leaders where this need becomes more pronounced for them. Therefore these watchouts and techniques are hopefully helpful for all readers.

Furthermore, many of us are likely to encounter affiliation dominant people on our teams and we can use these watchouts and techniques to coach them.

Some questions I reflected on this week:

What are some upcoming decisions where these watchouts may show up for me?

Who can hold me accountable for implementing one of these techniques and sticking to the insights that come out of it?

Who else would benefit from coaching on some of these techniques?

“Jon had a difficult time casting Robert, not because he was less brilliant, but because of RDJ's drug and drinking history, which made it difficult for the director to persuade the production house.” More here. Aside from being the lynchpin of the first 3 phases of the MCU, Robert Downey Jr.’s redemption story is also endearing.

After Hulk with Edward Norton Jr. was a flop, they needed Iron Man to ring the register…and it sure did…grossing $585 million worldwide and setting the stage for billions with the movies that followed.

As a reminder from last week, McClelland defines affiliation as the desire to establish, maintain or restore friendly and harmonious relations and a deep need to be liked and accepted.

For the purposes of these reflections, I’m distilling the perspective to the dominant motive. That said, it is worth pointing out that there is often an interplay between motives. In other words, you may see some differences in decision-making for leaders that are affiliation dominant but also have a relatively high achievement motive vs. those with a lower achievement motive.

I’ll likely reference this excellent book in subsequent reflections as it is a gold mine of practical advice on decision-making. While not all of their tools are science-backed, they are all very pragmatic, which wins the day for me every time. The trick is to experiment with the tools and see how they work for you rather than taking them as gospel.