“Hence, anxiety is the dizziness of freedom, which emerges when the spirit wants to posit the synthesis [of our potential and of the limits of real life] and freedom looks down into its own possibility, laying hold of finiteness to support itself. Freedom succumbs to dizziness.”

Søren Kierkegaard

We all say we want freedom…until we face a tough decision where all options are fraught with risk.

Kierkegaard called it “the dizziness of freedom.” This is the moment when three overwhelming realizations converge: 1) that we have too many options, 2) that we alone are responsible for choosing, and 3) that making a choice could result in massive discomfort for us and/or those we care about.1 In other words, it’s a philosophical predecessor to Morpheus, getting at the heart of what makes it so hard for us to “take the red pill.” (Shoutout to 1999 classic the Matrix)2

Leadership Principle: Values must guide your actions when the possibilities and obstacles feel overwhelming.

You’ve felt the dizziness of freedom at home, at work, in the world…What school to send your child to…how to grow your career…what bold investments to make in your business…when to speak up and do something about issues we care about.3

Leaders know this feeling well. It shows up when:

The data is inconclusive

The pressure is high

The timelines are short

The tradeoffs are hard to juggle

And the consequences of making the wrong decision feel existential

In those moments, most “decision-making tools” break down. Analysis is insufficient. Emotions and thoughts mislead. Advisors and others we trust disagree.

So what do we do in these moments?

We turn to values.

Values are so powerful, because they are inherently aspirational. They are the themes we want to live by when we are operating as our best self.4

They are also deeply personal. Values can lead different people to make different decisions when faced with the same set of options. That’s a beautiful thing.

Without clear values, the “dizziness of freedom” turns into intense vertigo, especially for the hardest decisions in each domain of our life.

The challenge for many people is that they haven’t taken the time to define their values.

Even when people have defined their values, they often fall into a common trap: their values reflect what sounds good or what others admire rather than conviction about what truly matters to them. The result is very little behavioral clarity. Values only work when they’re yours, when they’re clear, and when they show up in what you do under pressure.

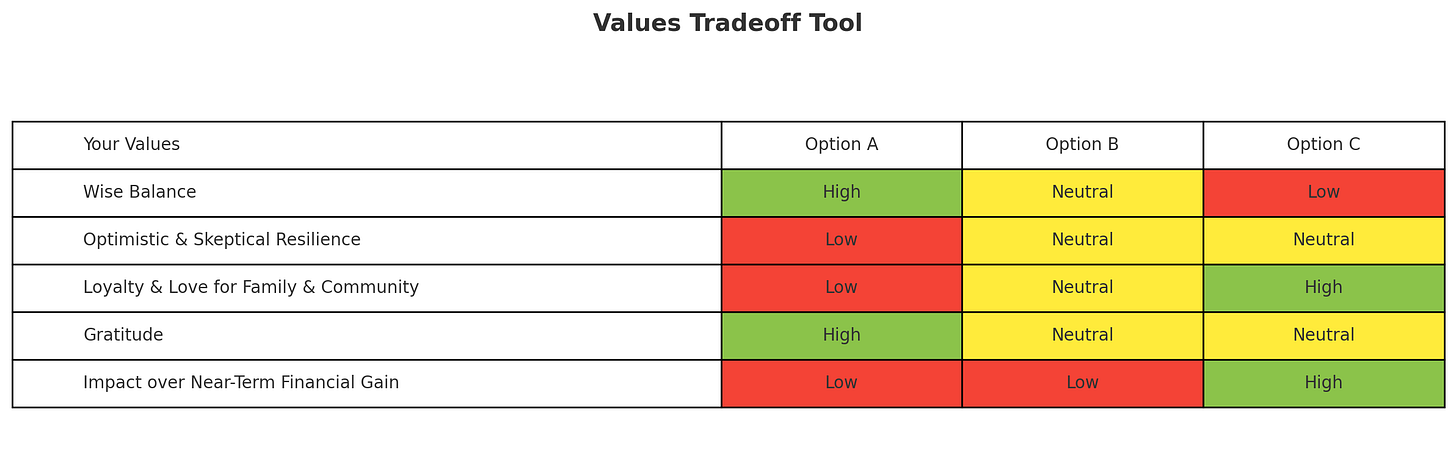

When values are clear, you can then weigh options against those values (see below for an example tool).

One CEO I worked with faced intense pressure to pull her company out of Russia at the outset of the Ukraine war in 2022. Most global peers exited quickly, and even some on her board pushed her to do so. But her company delivers healthcare solutions and she held a deep personal value: responsibility to vulnerable populations.

Staying in Russia would mean reputational risk and financial consequences. Leaving would mean pulling care from people who needed it and had no other way to get access. She made the decision to stay in Russia. It was painful, unpopular, and principled.

Values didn’t make the decision comfortable or easy. They made it clear.

For leaders, values turn freedom into a responsibility worth carrying.

Take Action: Proven and Practical Steps

Write down your REAL values. Not what looks good on a website or on your wall. They need to be what you stand for when pressure hits. I have found it helpful to define values with a blank sheet of paper rather than following a formula; however, some people benefit from structure. If you fall in that camp, here’s one tool. The key is to limit them to 4-5 values, avoid vague words and have confidence that these themes accurately reflect who you are and who you want to be. 5

Name and pressure test the tradeoff. You get clarity when you name the underlying tug-of-war in a decision: money vs. meaning, coasting vs. all-in energy, security vs. alignment. Name them early. Then test them since sometimes we create artificial tradeoffs by thinking too narrowly or too near-term. For example, money and meaning may come at odds within a short time horizon; however, there are many situations where money and meaning can align over a longer time horizon.

Evaluate the options against your values. Ask yourself: which option best reflects my core values, even if it feels scary or uncomfortable? For high-stakes calls, map each option against your values. Green = aligned, Yellow = neutral, Red = conflict. This makes the tradeoffs conscious and can help guide you toward a decision.

Reflect: Some Questions to Consider

What are your essential personal values? What are your business/professional values?

In what ways do you live your values? Where do your behaviors contradict them?

What’s an upcoming decision where you will need to rely on values to navigate the dizziness of freedom?

If this week’s Friday Reflection was practical or enjoyable (or maybe even both!), please share it with your colleagues and friends.

Over two decades ago, I read a book that spoke to deeply held principles AND challenged the narrow, fixed way I had been applying them. That book: Fear and Trembling by Soren Kierkegaard.

Above all, this book reinforced my belief that: people need to have an exceptional mission in life and to achieve that mission they often have to take a leap of faith.

And while for me, that mission is no longer associated with religion, as it was for Kierkegaard, I feel drawn to leadership and helping world class leaders be even better, because I see it as a powerful way to have a positive impact on the communities I care about.

Two decades later, I came across Kierkegaard again. The quote above on the “dizziness of freedom” is from a later work called The Concept of Anxiety.

The Matrix is still one of my favorite movies. And it’s hard to think of a better metaphor in decision-making than the blue pill or red pill one.

For example, I’m deeply troubled and angered by the Trump administrations’ attacks on foreign student enrollment at Harvard. I have the privilege of going back to campus for my 20th reunion this weekend, and I hope to get clarity on what role I can play to advocate for the university and for these students. At the same time, taking a strong position on a topic like this is not without risk for me professionally or personally, so I “agonize” about the “right way” to do it.

Jim Collins has an interesting related point to this which is thinking about what your unstated values might be. Ones that are less aspirational yet still essential to who you are. The question he asks to uncover these is: Suppose some researchers from another planet arrived and all they did was observe your actual behavior for a year, like studying some sort of strange species. And then based upon your behaviors, they had to say these are your essential values, because your behaviors would reflect the values in reality. In this construct, what would you say are your essential values?

If you plan to use them for personal and business decisions, then I suggest creating two sets of values. The leaders I admire most “live by business values with the same rigor and integrity as personal values.” While there may be some overlap, personal values and business values likely need to be different. For example, loyalty to family and community is an admirable personal value and yet in a business context, a similar type of loyalty can actually be damaging to performance and culture.